Prof. Pineda releases new novel

3 min read

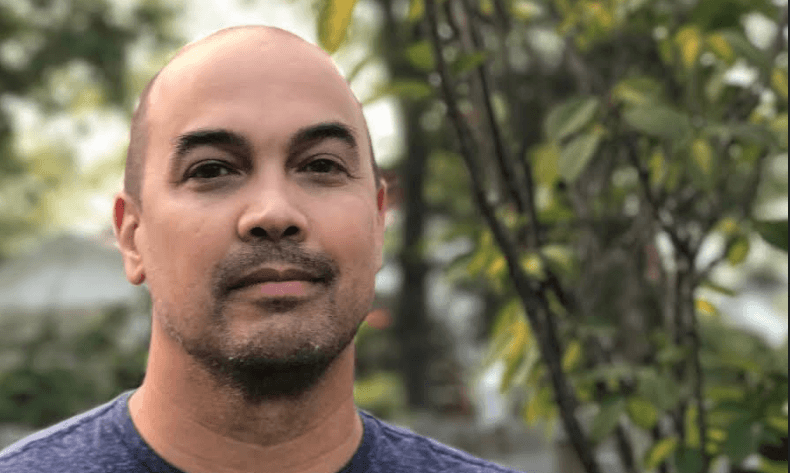

Shyan Murphy | The Blue & Gray Press

By GARY KNOWLES

Senior Writer

Beautiful things happen when you view life as poetry. You reach something intangible, raw and moving. Jon Pineda, a creative writing professor at The University of Mary Washington, does just that in his new novel “Let’s No One Get Hurt” that was released on Mar. 20, 2018.

The novel follows young protagonist Pearl as she wades through life in the deep South. Her family is a rag-tag bunch made up of Dox, Fritter and Pearl’s father. The three men and Pearl live in a shack near a river that belongs to someone else. The novel’s divided structure into small sections of detailed prose can be confusing at the start of the book. The sections often switch time and place, or simply continue the same scene as the previous section at a further point in its progression.

Despite this, Pineda weaves together the past, present and future in ways that walk the line of experimental fiction. Pearl’s journey shows that the past never stays there, and its tendrils creep up on us when we least expect it.

Pearl’s main qualm with the past is the abandonment of her mother. She tries to reconcile how her mother could have just got up one day and walked out on her and her father. Pearl goes back and forth between wanting her mother and refusing to become her.

The dynamic of abandonment that Pineda presents plays out in other ways throughout the book after Pearl introduces the concept. Pineda’s poetic attention to detail makes the reader frequently wonder when someone else could walk out of Pearl’s life.

Dox and Fritter’s story seems to parallel Pearl’s and Pearl’s mother’s story. In both cases the parent, Dox and Pearl’s mother, leave. Luckily for Fritter, his father comes back. While Pearl is left wondering what happened to her mother.

The central thread of abandonment continues with Pearl’s dad and his alcoholism. Her dad’s relationship with alcohol divides the two characters in ways that make Pearl sometimes feel left behind even though he never really left like her mother.

The story Pineda weaved together through Pearl creates a brilliant coming-of-age story that goes from one small, innocent girl not being able to put down her beloved dog, Marianne Moore, into someone who is ready to take on whatever is thrown at her.

Along with abandonment, Pineda brings up topics such as racism, understanding, gender, mental illness and self-esteem. These issues follow Pearl as she navigates the confusing life of squatting in a shack with three older men and constantly wanting to fit in with people her own age, which is something she never quite achieves.

One of the most remarkable things about Pearl is that she doesn’t fit into the tomboy role, nor does she come off as a girly-girl. Indeed, Pearl knew what she was talking about when she narrates, “I’m a poem no one will ever translate.”

Despite that statement, Pineda does a pretty good job translating Pearl and her world onto paper. The result is a character who never quite fits into a specific gender role or stereotype, but one who exists in all of them simultaneously.