Inhumane animal testing conducted in UMW laboratories should be replaced with innovative alternatives

5 min read

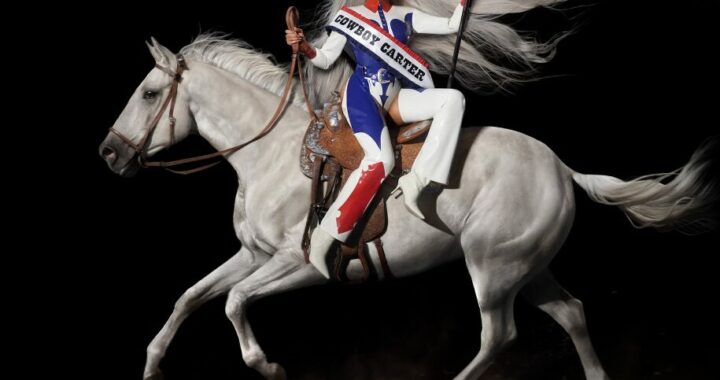

Caption and attribution: Unlike some other public universities in Virginia, like the University of Virginia and Virginia Commonwealth University, UMW is not accredited by the AAALAC. | Abbey Magnet, The Weekly Ringer

by ERIKA LAMBERT

Staff Writer

At UMW, particularly in courses focusing on animal behavior, some departments use animals such as mice and hermit crabs for research purposes. Beyond the specific research goals, there arises a moral question of animals’ rights being violated in the pursuit of knowledge and whether it is ethical to conduct research with the potential to induce stress or cause harm to a living being.

Animals deserve to live free from research tests that frequently yield insignificant outcomes, and the research conducted at UMW has had inhumane consequences on the tested animals, including heightened stress levels and fatalities.

According to a UMW student who spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid classroom retaliation, the conditions where these animals are kept are less than ideal. They described the spaces where these animals are kept, which they saw when a professor gave their class a tour.

“I saw that there were roughly 20 rats occupied in small containers, housing two rats each, with only bedding to occupy the confined space,” the student said. “It was obvious that the rats, eager to stretch and explore, were limited by the lack of room to move freely and the absence of any toys for entertainment.”

“Despite our professor’s reassurances about the animals being well cared for and having humane testing, the living conditions showed otherwise,” the student continued. “I don’t think it meets the standards of a proper, healthy environment for the rats when they are confined in a small container without space to roam or engage in playful activities.”

Despite guidelines recommending larger cages that accommodate a minimum of 370 square inches per mouse, the mice at UMW are confined in small cages that provide approximately 130 square inches per mouse.

The student weighed in about what changes they would like to see in these laboratory environments.

“Ideally, I would like to see UMW steer away from exploiting animals altogether. But at the very least, I would like to see a significant improvement in their living conditions,” the student said. “Larger cages equipped with enriching toys and an overall more caring environment would go a long way in ensuring some form of well-being of these animals.”

David Stahlman, an assistant professor of psychology at UMW, said that UMW does consider the ethics of their tests by submitting their plans to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. However, there are multiple issues in UMW’s IACUC committee, including real-time oversight—as veterinarians are mandated to check on animals for only two hours every six months—and bias from a policy that requires those with conflicting interests to leave during discussions and voting.

Most crucially, though, UMW’s IACUC lacks AAALAC accreditation—an organization that evaluates institutions against legal standards and promotes standards for animal care excellence. Attaining AAALAC accreditation would affirm UMW’s commitment to elevated standards in animal research. Other public universities in Virginia, such as the University of Virginia and Virginia Commonwealth University, are accredited by the AAALAC.

Supporters of animal research defend these experiments by emphasizing their potential and history to drive scientific progress.

“Research using nonhuman animals is critically important,” said Stahlman. “Any honest examination of the history of science and of medical technology shows this to be true.”

However, while animal testing was deemed necessary in the past, there have been significant advancements in scientific methods in recent years. Innovations like in vitro cell testing, computer simulations and organ-on-a-chip technologies now provide valuable data without resorting to animal exploitation.

Research methodologies constantly evolve, which was exemplified by the transition from animal testing for cosmetic safety to more humane and reliable alternatives, which led to 10 U.S. states banning the sale of cosmetics tested on animals. Furthermore, in the pharmaceutical realm, approximately 89% of drugs that pass animal tests fail in human clinical trials, and 50% of these failures are attributed to unforeseen human toxicity.

While proponents of animal testing argue that the benefits justify potential harm, a growing number of scientists and animal advocates question the scientific validity of such experimentation.

These ethical concerns extend to mice, which are sentient beings that experience emotions akin to those felt by humans. In a study conducted by UMW’s Department of Biological Sciences, researchers found that intermittent exposure to cat urine-soiled litter significantly induced anxiety-like behaviors in the mice.

During this study, the mice began to display defensive behaviors when exposed to cat odor, even when the litter wasn’t present through retreating, attempting to hide and becoming more rigid. One student noted that after three or four procedures, the mice would still display these behaviors, thus indicating that anxiety lasted beyond the initial experiments.

The mice in these experiments were then killed using cervical dislocation to dissect their brains. The study discovered that exposure to cat urine increased anxiety-like behaviors in mice, however, there were no changes measured in the brain factor they considered.

In another study, students separated mice into three groups with four mice in each unit, and another four mice were housed individually. The project’s primary objective was to assess the level of corticosterone—the principal stress hormone released in response to environmental challenges—in mice.

Although the study found no observed effect of social rank or isolation on corticosterone levels, it acknowledged the potential for environmental changes to induce stress, raising ethical concerns about exposing mice to situations that cause stress or harm.

Similarly, another study sought to inform how changes in mouse living spaces and exposure to overstimulation affect their memory and other brain chemicals. In the study, experimental mice were subject to daily habitat disruption for a week and then underwent the “Y-maze test,” which measures working memory. The mice were then euthanized through cervical dislocation to excise their hippocampus. The researchers concluded with statistically insignificant data, thus, ending the lives of the mice without achieving any meaningful outcome.

Encouragingly, a positive shift to initiatives that equip students with essential skills without causing harm to animals is apparent in U.S. universities. According to PETA, the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University and Western University of Health Sciences College of Veterinary Medicine successfully implemented humane and effective curricula for students, demonstrating the possibility of conducting research without the need for animal harm in veterinary education.

UMW’s website proudly declares that the campus experience “links a community of compassionate individuals who are ready to comprehend and contribute to the world.” Considering this, tolerating inhumane animal treatment at UMW does not align with the values of a compassionate community, and the University should pursue innovative alternative avenues for their students.